On stage in the Holy Land

By Maureen Gaddi dela Cruz

Thursday, 10, 17, 2002

“We all wish that culture will be the first priority, but as long as war exists in the world and people invest in weapons, it will never happen. So we try, we do our best.”

- Gil Alon

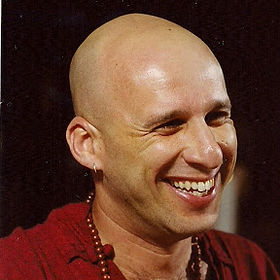

On Sept. 9, Israeli actor and Zen Buddhist teacher Gil Alon gave a lecture on Israeli theater at the Rockwell Condominium, Rockwell Avenue, Makati. The event was hosted by Her Excellency Irit Ben-Abba, the Israeli Ambassador to the Philippines. As Alon shared his own and Israel's experiences regarding theater as an art form, the multicultural crowd of diplomats, artists and art enthusiasts were held captive by his engaging and informative anecdotes. Like all accomplished actors, Alon proved to have a gift for enthralling his audience.

Aside from being a film and theater actor and television host, Alon conducts workshops on both Zen Buddhism and theater, and has represented Israel in various countries as a lecturer, actor, director and singer. He is currently on a two-year journey to expand his study of Zen Buddhist philosophy and its links with theater.

The lecture emphasized the vital role theater plays in Israeli life and culture. Not surprising, considering that Israel holds the world record for the largest number of theater productions per capita. This may seem remarkable to many, for whom mention of Israel probably conjures up images of Biblical figures, the Wailing Wall, or the long-standing conflict with Palestine. But in fact, the country's colorful history has produced a rich artistic tradition and a diverse, creative cultural scene that is very much alive in the face of socio-political change.

First do, then talk

As Ahron Shapiro writes in his article "Curtain Up" on jpost.com, it all began with Jacob. In a story from the Old Testament, Abraham's clever grandson is said to have started the theatrical tradition by dressing up in animal skins and pretending to be his elder brother, Esau. Jacob's performance was a success — it was so convincing that his blind father, Isaac, trustingly gave him the blessing intended for his brother.

Despite Jacob's early triumph, theater as an organized art form was not firmly established in ancient Hebrew culture. The history of modern Israeli theater actually began with the founding of the Habimah National Theater in Moscow in 1917. Fourteen years later, it moved to Tel Aviv, where it is now located. The other major theatrical institution in Israel, the Cameri Theatre, was also founded in Tel Aviv in 1944.

As Alon relates, however, theater in Israel is not isolated to the big cities like Tel Aviv. Government subsidy has made it possible for theater productions to be conveyed to remote areas at reduced costs. This, along with the abolition of censorship, Alon credits to the dedication of the nation's artists. He explains the kind of passion that goes into Israeli art: "First we do, then we talk. This is our attitude, not just towards art, but in general."

Perhaps the creative drive of a nation's artists is proof of its people's resilience. Israeli artists, as described by Alon, are able to make full use of their limited resources and still come up with world-class productions (some Israeli theater productions, like Yehoshua Sobol's Ghetto, have been translated into many other languages and staged in various countries). Contrary to the conservative outlook often associated with this country, creativity and enthusiasm abounds in Israeli culture.

Culture basket

Another key to the vitality of Israeli theater is the integration of artistic awareness into people's lives and consciousness. Early exposure to art is ensured by the so-called "culture basket" within the educational system. It guarantees that every student gets to attend a minimum number of theater productions, concerts, films, art exhibits, and the like during the span of his basic education. Youths can even join an Army theater group, as Alon did, when they commence the mandatory period of army service upon graduation from high school.

Private companies are required to subsidize the ongoing cultural education of their employees as well. About twice a year, large companies sponsor theater productions for their employees to attend.

But the celebration of creativity is most apparent in the theater festivals that abound in Israel. Some of these are held in schools, to encourage the emergence of fresh talent.

Artistic filter

Finally, Alon stressed the freedom and openness that accompanies Israeli art. Asked whether moral issues are a big concern in Israeli theater, he clarified that theater has in fact become a way to challenge societal taboos. He was also quick to point out that Israel, contrary to its conservative image, is actually a very secular society. The single most sensitive subject for the Israeli audience is, understandably, the World War II Holocaust. But, as Alon shared, he had in fact played the role of Adolf Hitler in one successful production.

This underscores theater's vital role in what Shosh Weitz in "The State of the Arts in Israel: Theatre", on us-israel.org, calls "provoking the national consensus." For Alon, it proves that controversial topics can be tackled in a work of art as long as the artistic quality of the piece is not compromised. "The main concern in Israel," he says, "is that theater will become a newspaper on stage. This means that you take a [socio-political] problem and put it exactly on the stage; that is considered very boring. There will always be a kind of 'artistic filter' through which the problem will be derived."

There have also been notable efforts among artists to bridge the gap between Israel and Palestine through theater. Alon told of a collaborative effort between the theater in Jerusalem and artists from across the Palestinian border, the Gaza Strip, to produce a version of Romeo and Juliet where Juliet is Jewish and Romeo is Palestinian. Yet as he points out, art cannot change politics, particularly in a situation with such deep historical roots. Still, the efforts continue, and theater continues to be a living institution – hopefully, in both cultures.

We are all artists

This cross-cultural sharing became food for deep thought for many Philipinos in the audience. Hearing of Alon's experiences causes one to reflect on the state of our own artistic scene, alive with potential and rich in its traditions, but all too often hampered by precisely the issues that Israel has recognized and constantly strives to address: lack of funds, insufficient government support, strict censorship, and most importantly, the difficulty of forging a strong, tangible connection with the people.

Israel's experience could be instructive to Philipinos involved in the cultural scene. Having given workshops in The Philippines and worked closely with our artists, Alon lauds the Philipinos' creative impulse: "Here I found such a deep will to experience, to learn and be open. When we start working, there are no differences; we are all the same – we are all artists."

With the permission from the Lifestyle Section, The Daily Tribune, Manila,

The Philippines.